Murder at the Devil's Elbow in Costa Rica

The hidden story of Costa Rica's path to army abolition.

Costa Rica is one of the region’s most-stable democracies. The country abolished its military and has experienced remarkably little political violence since the 1948 Civil War.

José Figueres Ferrer — who led the uprising, served as interim president, and proceeded to demilitarize and expand voting rights — is revered for his role in shaping modern-day Costa Rica.

Those accolades are well-deserved. But the reality of post-war Costa Rica, under Figueres’s leadership, is darker than many remember today.

Murder at the Devil’s Elbow

A bloody and turbulent 1948 ended with Figueres in charge of a provisional government junta. He was also participating in an assembly to draft the new Constitution, which would soon deliver prosperity to Costa Rica.

But peace and justice were no guarantee in a post-war Costa Rica, especially for those who had opposed Figueres.

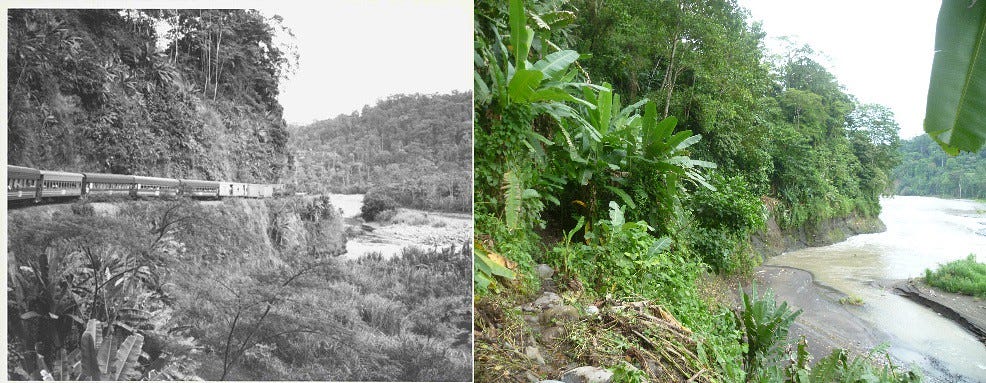

On December 19, 1948, eight months after the war had ended, six political prisoners from Limón were extrajudicially murdered by a group of soldiers at a place known as “El Codo del Diablo” — in English, “The Devil’s Elbow.”

The victims — Federico Picado Sáenz, Tobías Vaglio Sardi, Lucio Ibarra, Octavio Sáenz Soto, Narciso Sotomayor and Álvaro Aguilar — had ties to the Communist Party that had lost that year’s Civil War.

The six were handcuffed in order to be transferred to the penitentiary in San José. But near a sharp turn on the railroad known as “Codo del Diablo,” they were assassinated with a firearm and dumped into the Reventazón River below:

They were executed at close range by military officers of the de facto government of the Founding Board of the Second Republic in a place on the San José-Limón railroad called El Codo del Diablo, when by superior orders, they were transferred from the barracks of Limón to the Central Penitentiary of San José. … The crime is inscribed within the actions of repression and arbitrary persecution by the victors of the Civil War of 1948 against whom they called the Caldero-communists.1

The crime might’ve gone unnoticed, but one of the bodies washed ashore a few days later.

A trio were charged and convicted, but none served prison time. They instead fled the country — allegedly with the help of the new Costa Rican government.

A forgotten crime

The murder of six political prisoners may seem like a minor event in the overall arc of Costa Rica history. After all, Figueres and the new Constitution ultimately created a more peaceful country — one that prioritized healthcare and education over war.

But the events of December 19, 1948, force us to rethink the narrative of Costa Rica’s democratic past. Historian Antonio Jara, who directed a film about El Codo del Diablo, called the murders part of Costa Rica’s hidden story:

[Army abolition] became a narrative that’s just a little too heroic. The triumph of Figueres was accompanied by democratization and demilitarization. So, anything doesn’t fit within that narrative, well, it’s better to turn down the volume or say, ‘That wasn’t important.’

The abolition of the army was a political process that had a cost, and that included marginalizing and expelling from the political arena an important group of people. That separation from the political process of organizations of workers and leftist parties was done in an arbitrary and violent manner.

That violence, and the people who lost their lives, deserve to be remembered.

Support The Costa Rica Daily

The Costa Rica Daily is 100% ad-free, and we can only exist with your support:

Acuña, Víctor Hugo. (2014). Las memorias del Codo del Diablo. Revista Paquidermo.